The Political Structure of Ragusa

April 12, 2021

Following on from my previous post, this is part 2 in an ongoing series about the republic of Ragusa.

Ragusa, much like Venice, was an Aristocratic Merchant Republic. It had an interesting political structure that resisted being captured by any one powerful family, unlike in say Florence, and it also was able to maintain itself for 450 years without any major civil conflict. This was largely accomplished by having democratic institutions that broadly shared power around the nobility as well as explict safeguards in place to prevent it being captured by one person of family.

The description below is based heavily on a written account we have from 1605, but all of the major pieces were in place by 1360.

The Political Structure

The Rector

The Rector was the head of state of the republic. This position has its origins in the Venetian count who ruled the city in the days of Venetian Suzerainty. When Ragusa broke free from Venice with the help of Hungary, the venetian count was originally going to be replaced with a Hungarian noble, but after some subtle diplomacy, they were able to convince the Hungarian king in 1358 to allow themselves the right to choose who they wished as count. Thus the development of the elected position of Rector. Initially this was envisaged as a role shared by three elected positions, having two month terms where each lived for one week in the Rectors apartment in rotation. This was streamlined for fairly obvious reasons to its final form: a single elected position with a one month term.

Despite all the context above, the Rector was still the head of the government. He held the keys to the city gates and fortifications, kept the passwords to enter them, and was in charge of the seals of the Republic. He alone had the authority to summon the Senate and the Great Council, proposed their order of business and signed all public acts. No act was valid without his approval, but, on the other hand, he could not make decrees without the assistance and consent of the councils. The actual power of this position outside of the small council was fairly small, but the position was considered to have moral influence and the Rectorship was highly valued as a mark of honor.

The rectorship came with all of the pomp and ceremony you would expect from a head of state. While holding office you dressed in a red toga and wig in the Venetian style1. You also were expected to live in an apartment in the Rector’s Palace and only leave it on certain prescribed occasions, during which he would be preceded by 24 twenty-four heralds.

Conflicts of interest were taken seriously by the republic. If the Rector or his family had some private interest in a matter convention dictated that he was to exclude himself with the oldest member of the small council taking his place.

To be eligible to be elected as Rector you had to be a member of the Senate and be at least 50 years old. You would be elected for a one month term before entering a two year cooldown period where you were not eligible to be re-elected. There was no limit in the number of times you could hold the position, so a long-lived noble might hope to be elected as rector on a number of occasions. For example Luciano di Girolamo Bona was elected to be Rector 8 times.

The Small Council

(Consilium minus, Minor Consiglio, Malo vijeće)

The small council assisted the Rector in running the republic, having a role much like the privy council found in other political systems.

It acted as the general intermediary between private individuals and the State and some of its duties included:

- Receiving ambassadors and other distinguished visitors

- Arranging all official ceremonies

- Reading correspondence from Ragusans abroad

- Receiving petitions

- Giving leave for appeals in civil matters

- Issuing safe-conducts for debtors

- Examining the deliberations of the other bodies on taxes, dues, and the rents, income, and real property of the State.

- Appointing trustees and guardians for widows and orphans.

- Hearing complaints against other officials or magistrates.

While the Senate was ultimately responsible for foreign policy, the youngest member of the Small Council did act as a kind of Foreign Minister. The small council would also discuss matters of public interest but only carry out a prelimnary discussion before reporting to the Senate.

The small council was elected and consisted of the Rector and eleven other members, five of which formed the High Court of Justice for hearing important cases. The members were all men of mature age, and remained in office for a year only. Only a single member of a family was allowed to serve on the council at at time. Six made a quorum.

The Senate

(Consiglio di Pregati / Consilium Rogatorum) also known as the ‘Fathers’ (Senato de’ Padri) or the ‘Council of those Asked’ [i.e. by the Rector to attend]

This started out as a consultative body but by the 16th century had become the real government of the republic.

- It imposed all taxes, tributes, and customs duties, regulated trade, audited accounts, and decided how the money of the State should be spent or invested.

- It supervised security and acted against those who threatened order. It also took over all the main foreign policy functions, appointing and instructing ambassadors and consuls as well as judging their conduct.

- It appointed a number of State officials.

- It was the Supreme Court of Appeal for criminal cases, reviewing capital sentences with the ability to grant pardons. It also heard civil cases involving more than 150 ducats, with no appeal being possible from its decisions.

The Senate had sufficient business that it was meeting four times a week, and there was so much work in hearing civil case appeals that it prompted the creation of the College of Twenty-Nine, a civil court of appeal for cases involving 150 ducats or less.

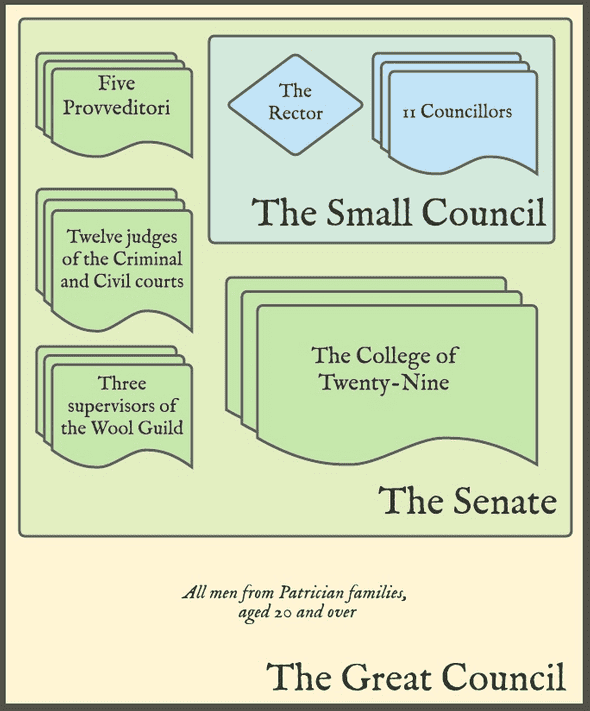

The number of Senators varied considerably over time, but at the start of the 17th century it included

- The Rector and Small Council

- The five Provveditori 2

- The twelve judges of the Criminal and Civil courts

- The three supervisors of the Wool Guild

- The members of the College of Twenty-Nine

People remained in office for a 1 year term with the possibility of being reelected with no cooldown period. This allowed experienced senators to serve uninterrupted which added stability to the body. By a decree of 1331 it was decided that thirty Senators made a quorum.

The Great Council

(Consilium maius, Maggior Consiglio, Velje vijeće)

This was the sovereign governing and legislative body which elected the other councils, officials, as well as the Rector. The Great council ratified all laws of the republic, and had final say over declarations of war and peace. It received petitions and managed many of the daily affairs of running the city. Sixty members, including the Rector and the small Council, formed a quorum.

This council consisted of the entire noble class all males for noble families over the age of 20 were eligible to attend (this was reduced to 18 in the wake of the 1667 earthquake). Similarly to Venice, the nobility and hence membership in the council and political system was closed in Ragusa in 1332. This is to say that pool of noble families was fixed, strict prohibitions between intermarriage with lower classes were put in place and there was no mechanism to onboard upwardly mobile families into the aristocracy. Eligibility was made perfectly legible starting in 1440, with a book called the mirror or Specchio containing the name of every man eligible to attend the great council.

By the late 1500’s there were around 250 of these councilors, with between 100-200 turning up to any given meeting.

Elections

The election process in Ragusa features and interesting mix of sortition and the secret ballot, but I will save a description how elections were run to a later post.

This post is largely based up the the following sources:

Harris, Robin. 2006. Dubrovnik: a history. London: Saqi Books.

Villari, L. 1904. The Republic of Ragusa: An Episode of the Turkish Conquest. J.M. Dent & Company.

These texts are drawing very heavily upon the following

Giacomo di Pietro Luccari, 1605. Copioso Ristretto Degli Annali Di Ravsa. Libri Qvattro.

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be an easily available English translation. I have roughly translated some sections and may throw them up on this blog at some point in the future.